Google search, April 4, 2012.

Google search, April 4, 2012.

Imagine you're visiting a foreign country where you don't speak the language of the natives. You can buy a guidebook and memorize a few phrases, or hope your smartphone can translate for you correctly. You can do what people have traditionally done in such situations, which is to learn how to say “How do I say...” and point and smile and hope people will be kind to you. Or you can do another thing people have traditionally done, with less success, which is to talk louder, gesture wildly, and hope that volume equals effective communication.

Searching the web is, for most of us, a little like visiting a foreign country. Search engines do not speak English. They don't speak any human language. They're machines. If you shout and wave, you'll probably manage to get something across to them, and you'll certainly get some information back. But it likely won't be what you wanted. To get what you want from them, you'll have to learn to speak their language.

It's true that some search engines encourage you to use “natural

language” queries — to type in an ordinary question, as you'd ask

another person. But these questions have to be translated to the native

language of search engines before they can perform your search — and

that translation is also done by machine. These programs are getting

better, but they're still far from perfect. As an example, here is a

portion of the previous paragraph translated first into Russian and

then back into English using the online service Babylon:

Not bad for a machine, but you'd be better off learning some Russian.

In practice, good searching (like foreign language fluency) can get to be a little complicated. Let's look at a real-world example and break it down.

Suppose you have a student who has very little eyesight, and you want to help guide her to websites for research that she'll be able to use fully, without too much frustration. If you were asking a question, it might be this:

How can I find websites for my blind student to do research?

If you type that into Google, you get websites with lists of blind bloggers, something about legal writing, a biography of Helen Keller... Clearly that isn't going to work.

To talk intelligibly to a search engine, you need to construct a search query. A query (which is just another word for question) describes in concise, exact, machine-readable language what you want to know. The first step is to identify the main idea or ideas behind your question.

How can I find websites for my blind student to do research?

The words we underlined are our keywords. Notice that we didn't underline the pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, or other small words. A search engine will typically ignore those words, because they're so common and almost never relevant to anyone's search, but it's usually best to leave them out anyway, so that they don't get in the way of your main ideas. Nor did we underline the word that describes what we're trying to do (“find”). Your students would similarly ignore words in their research assignments like analyze, evaluate, determine, and so on.

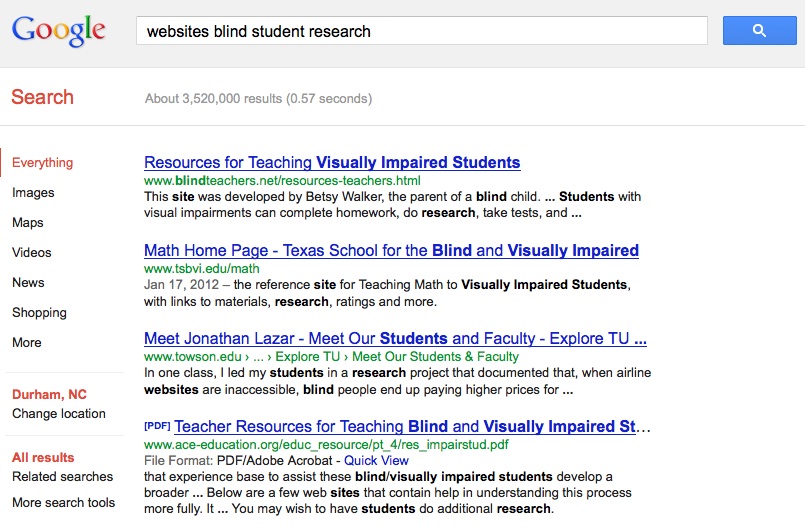

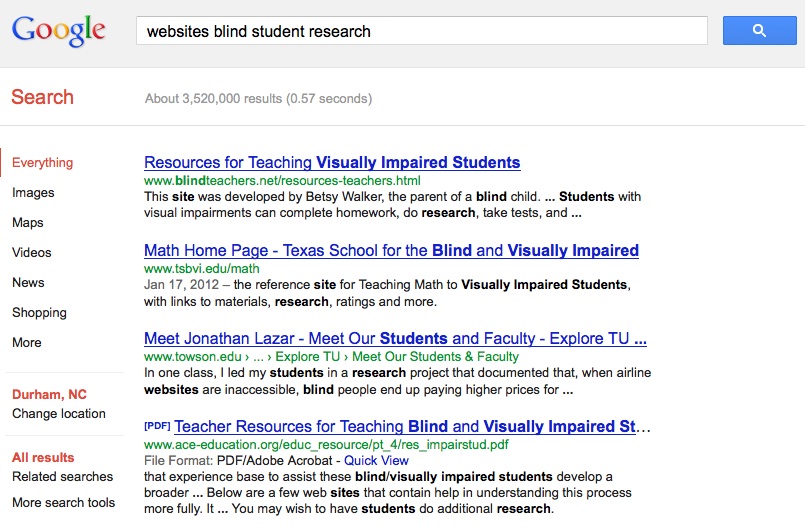

Now we'll try searching for our keywords. We'll use Google first, since it's the most popular web search engine. Type this into Google, or follow the link:

websites blind student research

What did you find? Do the websites on the first page of results answer our question?

Google search, April 4, 2012.

Google search, April 4, 2012.

Most of these pages clearly don't address our question. Most seem to provide fairly general information about teaching the blind. But sometimes the results you get from your first search will give you clues to help you find better keywords. In this case, the first results mention visually impaired — a phrase we might substitute for “blind.” A couple of the websites that come up have the word accessibility in the title or desscription. Accessibility (as you may already know, or might quickly learn) means how well people with disabilities can use a website, and so it might be a good addition to our keywords. You might also notice that “research” in the website descriptions seems to refer to research on visually impaired students, and so we might be better off leaving it out.

Now try this search:

websites visually impaired student accessibility

How do the results on the first page differ from those we got from our previous search? Is this better or worse, do you think? (It seems to be a lot of sites about designing websites for the visually impaired.)

It's also worth trying the words in different orders. Search engines often assume that you've typed the words in the order they occurred to you, most important first. Try this instead:

accessible websites visually impaired student

That gives us different results, but not necessarily better ones.

As we're learning, the forms of the words you use matters. If you search for formal and academic terms (“visually impaired” instead of “blind”) you're more likely to get formal and academic results. That's great if you're looking for published research. At other times, though, you may want less formal results. You may decide that the most useful information would come from blogs, discussion forums, or online rating sites.

![]() A good guideline is to imagine the page that contains the

answer to your question. What does it look like? What is its title?

What words appear most prominently and most often? Those are your

keywords.

A good guideline is to imagine the page that contains the

answer to your question. What does it look like? What is its title?

What words appear most prominently and most often? Those are your

keywords.

Remember also that not everyone will think about this concept the way you do. They may describe it differently. As we found above, sometimes your search results will point you to better keywords. If you don't quickly find what you're looking for – or maybe even if you do – try using a thesaurus. You may have one in your classroom or even on your computer, but you could also try a “visual thesaurus” on the web that shows the relationships between words.

![]() Take a few minutes and try out Visuwords

(http://www.visuwords.com/), which displays the relationships between

words graphically. Try some of the keywords from the search we've been

using — blind and student — and then try some of your own.

Take a few minutes and try out Visuwords

(http://www.visuwords.com/), which displays the relationships between

words graphically. Try some of the keywords from the search we've been

using — blind and student — and then try some of your own.

Finally, even tiny differences in word forms can change your search results. Most web search engines will automatically look for different forms of words, but they may not rank the results the same way. Try a plural word instead of a singular, or remove the “-ing” from a word. If you replace “student” with “students” in our query above, for example, you'll notice subtle differences in the ranking of the results. For a more vivid example, try searching for “digital literacy” and “digital literacies”!

For our search, above, we might decide that if we were going to answer our own question, we'd provide a list of the best websites for blind students. If the list was based on personal recommendations, it would probably say “blind” instead of “visually impaired.” So let's try this:

list best websites blind students

One of the first results is a list of sites for blind gamers, so we're getting closer. We might also try for more general understanding: “Here's how to tell if a website is accessible to the blind...” It's hard to reduce “tell” to a keyword, so let's just try typing in the entire phrase:

how to tell if a website is accessible to the blind

On the second page of results, there's a site explaining how blind people read a website using a screen reader. That's the most relevant website we've found so far, and we could continue refining our search by selecting keywords from that page (such as “screen reader”).

Sometimes, despite your best efforts, you'll keep coming up with irrelevant results. When we searched for “accessible websites visually impaired students,” for example, we found a lot of information about designing accessible websites, which we didn't want. We can try to remove those results by excluding a keyword from our search, by adding it to our query with a minus sign in front of it.

accessible websites visually impaired students -design

The minus sign is what's called a “Boolean operator” — an operator, or symbol that operates on a word, and that relates to a branch of mathematics called Boolean algebra. (See the supplemental links below if you're interested in learning more about Boolean algebra.) What we're telling the search engine is that we want to find these words:

...and not to find this word:

Notice that “visually” and “impaired” are separate words in this list! A good web search engine will prioritize results that list your words together or near one another, and if it can match some of the phrases in your query, it will. But you can require it to look for an exact phrase by enclosing that phrase in quotation marks:

accessible websites "visually impaired" students

In this case, “visually impaired” is such a common phrase that requiring that exact phrase doesn't make a lot of difference. But try this instead:

accessible websites "visually impaired students"

How does that differ from our previous results?

If one of the words in your query is very important, you can require it by marking it with a plus sign:

accessible websites visually impaired +students

By default, most search engines look for all the words in your query, so this may not help you. Occasionally, though, a search engine will ignore one of your keywords, perhaps because there are lots of results with all of the others, but not many with the keyword it excluded. If you find that one of your keywords isn't showing up in the results, try requiring it with a + operator.

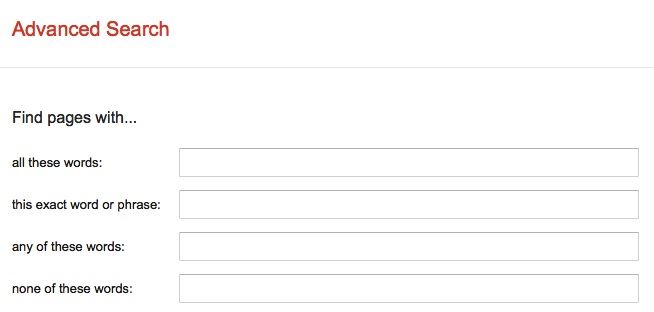

Finally, we should point out that this kind of complex searching is most useful in something like a library database. There, instead of using operators (+, -, and "), you may see an advanced search form something like this:

Google's advanced search form.

Google's advanced search form.

The concept is the same, though. Start with a basic list of keywords, and then refine it based on the results you get, requiring and excluding words or requiring exact phrases as necessary.

![]() For a simple way

to play with Boolean searches, try Boolify to see quickly how changing

the order of words and using Boolean operators can change your results.

For a simple way

to play with Boolean searches, try Boolify to see quickly how changing

the order of words and using Boolean operators can change your results.

What have we learned from all this? We tried several different searches, and we found a few sites that pointed us in directions for further exploration – general guidelines and means of evaluating websites. We didn't find exactly what we wanted, but we know how to keep looking. And if we decide it's time to find an expert to ask for help (because not everything is available on the internet!), we have a better sense of what kinds of questions to ask.